A Michigan problem: Too many deer + too few hunters = stressed farmers

Published in Business News

When Logan Crumbaugh was growing up on his family’s farm in Gratiot County, Michigan, spotting a deer was a rare and special occasion.

But these days, he and other farmers in Michigan's Lower Peninsula are seeing way more bucks and does crossing their fields and devouring crops in a feeding frenzy that's due in part to the declining popularity of hunting. The Michigan Department of Natural Resources says it’s hard to precisely estimate the statewide deer population, but some estimates range from 1.5 million to 2 million.

“Now you can't look outside without seeing a herd of deer run across the fields,” said Crumbaugh, 29. “You can’t drive around at night without seeing 20, 30, 40 deer out in any given field. And they're just everywhere. It's causing so much economic damage.”

Chad Stewart, cervid and wildlife interactions unit supervisor for the DNR, said it's "a safe assumption to guess that we have certainly well over a million here in the state. We're probably closer to over a million and a half deer. Now, how much more it goes beyond that, I don't know."

But the number of hunters is not keeping pace with the growth of the herd. According to a 2024 deer harvest survey report released in June by the DNR, 604,088 hunters purchased licenses in 2024, a 31% decline since 1995. For all seasons combined in 2024, 532,926 people hunted deer, up 1% from the previous year. About 360,000 deer were hunted in 2024.

Some farmers are calling for expanded hunting access on private land or incentives to encourage deer management hunting. In a June 2024 memo, the DNR cited increased private land ownership as a factor in the Lower Peninsula's surging deer population, along with fewer hunters.

The DNR and the state Natural Resources Commission have been taking steps to address the issue, including making it easier for farmers to hunt deer to prevent crop damage.

200 deer, one field

The state's increasing deer population in the southern part of the Lower Peninsula is affecting agricultural areas throughout the region.

“Farmers used to be able to see ... you drive down the road and see 10, 20 deer,” said Andrew Vermeesch, legislative counsel for the Michigan Farm Bureau. “Now we’re seeing 40, 50, 100. We’ve got cases, areas of the state where we’re seeing more than 200 deer in one field. We can all agree that is way beyond the comfort level and the desired threshold where we want to be.”

Farmers report hundreds of deer destroying crops nightly, causing significant financial and agricultural loss, said Ben LaCross, president of the farm bureau. He spoke of the plight of one soybean farmer in Mason County.

“Every night in a 40-acre field, he would count 100 deer eating his soybeans,” he said. “They basically destroyed the whole crop. I've had farmers down in the southwest portion of Monroe County talk about similar things. Hundreds of deer, dozens and dozens of deer in a small field, completely devastating the entire crop. No matter where you go, our farmers are facing challenges like this.”

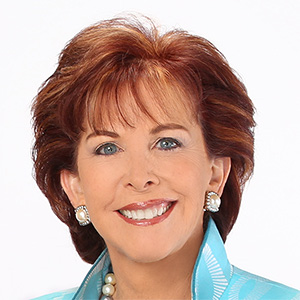

LaCross, a fruit farmer with 25 years of experience, says the deer problem has worsened significantly during his career. He attributes part of the issue to changing hunting culture and declining hunter numbers: “Over the course of time in my career, it seems like we’ve changed the culture of deer hunting. Now the culture of hunting is hunters only want to take big trophy deer."

Meanwhile, female deer reproduce early and throughout their lives.

LaCross said that while antler point restrictions were intended to grow bigger bucks, they contributed to a rise in the deer population. Leelanau County, where LaCross farms, was an early adopter in 2003 of the state’s antler point restrictions, which require hunters to hunt bucks with at least three points on one side, and four for a second buck, to promote older, larger deer.

“Hunters just aren’t harvesting enough deer to keep the population stable in the state," he said.

At one point, Crumbaugh said, crop damage caused by deer was costing his farm $700 an acre. He said other farms in the area were losing up to $1,500 an acre.

"It's certainly something that we factor into a lot of our decision making on the farm, knowing that it is a problem we have to deal with at the end of the day," he said. "Can't dwell on it too much other than just focus on a problem and continue to hunt and do what we can to protect our farm."

The consequences aren’t just economic. Increased deer numbers raise risks for communities as well, including more vehicle collisions. It's also a disease risk among animals, such as bovine tuberculosis, Vermeesch said.

Fences cost thousands

Many farmers have turned to physical barriers to protect their crops. Wire fencing, often six to eight feet tall, can help keep deer out, but it comes with a high price.

“It costs tens of thousands of dollars to fence just a few acres,” Crumbaugh said. “And it’s not just the initial cost. You have to maintain it, repair damage, and it can limit how you move equipment around the farm.”

LaCross said: “On our farms, the deer damage problem got to be so bad that for the past 10 years, any new orchard that we plant, we put an eight‑foot‑high woven‑wire fence around that whole orchard, and that’s an expensive process for us as farmers.”

There are also other consequences of the fencing strategy, he added: “But then what it does is it funnels those deer into the neighborhoods that surround our orchards. And our neighbors don’t like it, because then the deer eat their shrubbery and their bushes and their flowers."

Other deterrents include repellents, noise devices and planting strategies to minimize attracting deer. Farmers say they need a multi-pronged approach.

A decline in hunting participation has made it difficult to control the deer population. Michigan has lost roughly 30% of its hunters since 2000, said Stewart with the MDNR. Wildlife managers and farmers say hunters play a critical role in controlling the deer population.

"A huge explanation for some of the trends that we're starting to see is that we just don't have the same number of people managing deer the way that we've had historically," Stewart said.

'Buck-centric mentality'

In recent years, MDNR has expanded its hunting licensing to include female deer, without requiring an extra license. It's also increased the number of deer that can be hunted and extended seasons.

"What we've got to show for that is really not a whole lot of change," Stewart said. "What we're seeing is that in many instances, deer hunters are happy to take anywhere between one and two deer for the season. And there's a definite buck-centric mentality from a management standpoint. So hunters like to shoot the male deer with antlers and from a population management standpoint, that doesn't really move the needle a lot in terms of population size."

Stewart said what has promise is hunting to fuel a venison donation program. The Hunters Feeding Michigan program connects hunters and deer processors with food banks.

However, it has its challenges. The number of deer processors has declined by about 25% in the last five years, Stewart said. Processing a single deer can cost $100–$150, making it financially challenging for hunters or organizations to donate the deer and cover the associated costs. More funding is needed, he said.

The state issues deer damage permits to farmers seeking to shoot deer damaging their farms. Stewart said last year, 10,000 deer were shot on deer damage permits, and the requests for permits have increased in southern Michigan by more than 100% in the last five years.

"We're seeing a significant increase in demand for these types of permits associated with crop damage," he said.

The farmer, or permittee, can shoot a specified number of deer or call in assistance from an authorized designee, including hunters. The permittee is expected to make every effort to process deer for food, which can be a challenge during the summertime.

"It's a significant time investment to simply manage your crops," he said. "So none of these solutions are easy."

Crumbaugh said before implementing deer damage permits five years ago, the family's farm lost about 50% of its sugar beet crop on 80 acres. In addition to sugar beets, they grow corn, soybeans and wheat. He says his father primarily handles the hunting, although they have the option to hire it out.

The strategy isn't a cure-all, but has helped reduce losses, Crumbaugh added: "In moderate to severe cases, I would say we're losing probably anywhere from $300 an acre. We could lose up to $700 an acre in heavily impacted areas."

Hunter Jerry Gaca, 65, helps manage deer populations on two farms in Grand Traverse County, harvesting a total of about 15 deer each year.

“That seems to be a good balance, so that we're not taking too many out, but we are saving the farmer quite a bit of crop damage,” he said. “And we try to do it early, when things first start growing, as opposed to later in the season when they've already done their work. Even though you're taking them out, you've lost a lot of crop. The trick is to do it early.”

Gaca said he hunts responsibly and harvests all of the usable meat for family and friends: “I love the hunt. I love the shooting. I spent a lot of time outdoors, and it's just a way to extend my hunting season, makes farmers happy and fills my freezers.”

'It's not sustainable'

One resource for farmers is the Hunt Michigan Collaborative, which was established in 2024 to help mitigate crop damage caused by deer in the Lower Peninsula. The organization also educates and helps encourage hunting in the state.

The program is working with a handful of farms in the southern part of the state, connecting them with hunters to help with deer management, said Bryan Farmer, founder of the collaborative.

“We really want to help spread that word to get more people into the outdoors and the opportunity to learn and to get into hunting," he said. "And at the same time, help out (with) this larger issue of overpopulation of deer in many areas."

In 2024, the pilot program organized four hunts involving 43 hunters, resulting in 25 harvested deer, with 20 donated to food banks through partnerships with Hunters Feeding Michigan and Michigan Sportsmen Against Hunger.

“A lot of people are willing just to help that farmer out, and then that food from that goes to food banks,” he said.

This year, Farmer said the program has expanded to five farms and 16 organized hunts, each allowing 12 hunters. The effort is also partnering with private landowners and nature preserves to increase access. Looking ahead, he said they plan to ramp up to 20 farms and 100 hunts in 2026. In 2027, the goal is 40 farms and 200 hunts, potentially involving 2,400 hunters total.

Farmer said the collaborative is expanding this year to farms in Kalamazoo County, Central Michigan, the Thumb region, and the southeast, including Washtenaw, Sanilac and St. Clair counties.

Hunters receive two antlerless deer tags. The idea is to feed people in need, help farmers, provide access to hunters and attract new hunters. The program also seeks to diversify hunting participation.

“Now it’s really spreading out to different ethnicities,” he said, “We’re seeing Hispanic, Black, Asian, women, children. So it really opens it up to a lot of opportunities for organic food and managing the natural resources at the same time.”

On his family's farm, Crumbaugh continues to keep an eye on his crops through the planting and harvesting season. The deer damage permits seem to help, but he'd like to see more done when it comes to deer management, including more hunting of female deer and increased efforts to harvest and donate meat to people in need. For some farms, it's a matter of survival.

“It is possible to coexist with them, but the populations have to be way down from where they are,” he said. “It's not sustainable for the deer population. It's not sustainable for farming. It's not sustainable for Michigan to continue to have this problem.”

©2025 www.detroitnews.com. Visit at detroitnews.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments