Minnesota offers new protections to control 'staggering' amounts of personal info

Published in Business News

Minnesotans can obtain more information about how companies use their personal data, and the right to demand corrections or deletions, under a new state law taking effect this week.

The law allows consumers to request to see their personal data maintained by a company. It’s unclear how quickly businesses will be prepared to comply with it, but the Attorney General’s Office is increasing staffing in anticipation of new complaints requiring investigation.

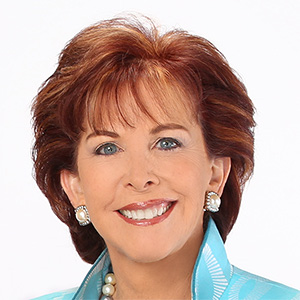

During a news conference outlining the new law Monday afternoon, Attorney General Keith Ellison said data is being monitored and stored in “staggering” amounts. He said the average person generates the equivalent data of 2,000 smartphone pictures per day.

“That’s a lot of data, and our inability to control where it goes, how it’s used, who gets paid for it, who gets to invade our privacy, is a big deal,” Ellison said.

Businesses or other legal entities required to comply with the law must have a webpage outlining privacy rights with instructions on how to make requests and exercise rights afforded under the law. A parent or legal guardian may also make a request on behalf of a minor younger than 13 years old.

The state set up a new website, privacymn.com, to give consumers and businesses a better understanding how the law will work. It also includes specific templates for users wishing to request data deletion, list entities to which data was sold, opt out of data collection, obtain a copy of a consumer dataset, confirm if a company processes specific data, question decisions appearing to profile consumers or edit a dataset.

Chief author Rep. Steve Elkins, DFL-Bloomington, said it’s time for more oversight on the troves of personal information consumers provide to businesses, knowingly or not. That includes data harvested by seemingly free applications like weather apps, which may sell the information to turn a profit.

“There’s an old adage around these applications,” Elkins said. “If you’re getting the product for free, you are the product.”

Consumers may also share such information willingly to gain access to products and services, without paying much attention. The data can be used to develop targeted advertising campaigns for various products and, in some cases, may determine a person’s eligibility for housing or insurance services.

Some consumers may question how companies use their answers to draw conclusions, and whether an analysis or inference may be inaccurate. Data privacy advocates are increasingly calling on state and U.S. lawmakers to take up the issue and create pathways for enhanced transparency and accountability.

Elkins worked on the law for five years. He said some provisions were modeled after the Fair Credit Reporting Act, which lets consumers see negative strikes against their credit kept by major credit bureaus Experian, Equifax and TransUnion.

“If you got turned down for an apartment or for a favorable insurance rate or a job and the company is just telling you, ‘Sorry I can’t tell you that’ — now, they have a responsibility to tell you,“ he said.

The state law applies to legal entities that control or process the personal data of 100,000 people or more; or those that control 25,000 consumers’ data and gross 25% of annual revenue from its sale. It contains specific exemptions, such as any government entity or a federally recognized tribe.

Since other states have passed various data policy requirements, some businesses are well-prepared to handle the changes. Others, though, may be less prepared.

The state generally offers a grace period with respect to new consumer protection laws and asks for compliance if violations are suspected or discovered.

Minnesota’s law is kicking in as scrutiny over private data use is growing. Many Americans have little understanding and much suspicion about the way private companies collect and use personal data. More than 80% of U.S. adults are concerned about those practices, according to a 2023 survey from the Pew Research Center.

A New York Times investigation last year illuminated consumer data practices of General Motors through Smart Driver, a standard feature on new vehicles capable of advanced surveillance. The collection and sale of specific information like detailed braking and acceleration patterns caused some drivers to see higher costs for insurance. Some said they were unaware or did not provide consent.

GM’s practices attracted scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission and state attorneys general, including Texas’, who sued GM in August alleging deceptive and misleading practices.

The Big Three car maker discontinued its Smart Driver program after the backlash. In reaching a settlement agreement with the FTC in January, GM promised to obtain “affirmative consumer consent” in order to collect, use or disclose certain data.

Congressional lawmakers have discussed, but failed to advance, any comprehensive federal protections for personal consumer data. Minnesota is among 19 states that have passed relevant laws. Elkins said Minnesota’s law borrows from other states’.

Nadeem Schwen, a Minneapolis data privacy attorney, said personal data is often being shared in ways an average person would not know. Many privacy laws like Minnesota’s aim to address the questions like how transparent a company should be in collecting and sharing information and what would a reasonable person not want to happen.

Personal information is also of high value to criminals. Companies that carry sensitive data frequently need to enhance cybersecurity to ensure personal information does not fall into the wrong hands. Last year, two data brokers were convicted on federal charges for selling the personal data of millions of consumers, often older and vulnerable Americans, to known fraudsters.

Controllers of personal data will also need to adopt practices that ensure personal information is not kept beyond its usefulness.

Under Minnesota’s law, the attorney general may take legal action against businesses that do not comply with consumer data privacy requirements. However, the law does not extend a private right to sue.

©2025 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments