Online sleuths or streaming ghouls? Baby Emmanuel case unleashes army of internet vigilantes

Published in News & Features

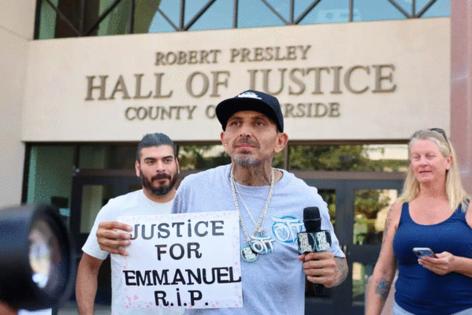

Attorney Vincent Hughes was swarmed by reporters and self-proclaimed TikTok journalists when he exited the home of Jake and Rebecca Haro, who’d just been arrested on suspicion of killing their infant son, Emmanuel.

Onlookers heckled him with boos and insults. One man streaming from his phone barked out a question.

“How does it feel to defend a murderer?” he said, before turning the camera back on himself and telling his viewers: “I just asked him the question.”

In the last couple weeks, the case of missing 7-month-old Emmanuel Haro has been a clarion call for independent journalists, online sleuths and criminal case followers — some of whom traveled across the country to California to chronicle developments.

They have set up lawn chairs outside the Haro home and livestreamed; some have gone up to the door and knocked.

The internet sleuths pick apart the trickle of information being released by authorities, often filling in the holes with rumor, speculation and innuendo. (For example, Hughes was Jake Haro’s attorney in a previous criminal case but is not representing him in the one involving Emmanuel.)

It’s gotten so bad that at a recent news conference, Riverside County Sheriff Chad Bianco called out the “keyboard warriors” following the case and sharing unverified updates or spreading misinformation.

“The problem that we are having ... is someone posts something on social media and then y’all believe that it’s true,” Bianco said.

The rise of social media has fundamentally changed the way crime buffs follow high-profile cases. One early example was the Golden State Killer case, where unsolved serial murders around California became an obsession to people across the country and helped push officials to keep focus on and eventually solve the case. The grass-roots detective work was chronicled in Michelle McNamara’s bestseller, “I’ll Be Gone in the Dark.”

When Hannah Kobayashi, of Hawaii, went missing after landing at Los Angeles International Airport last year, the internet went to work trying to find her. Their efforts brought global attention to her case, but also caused problems for police and family members. Some sleuths claimed she had been murdered or was the victim of human trafficking. In the end, police said she had left of her own volition and gone to Mexico. No foul play was involved.

In the case of Emmanuel, officials expressed their own frustrations with the freelance investigating.

“There should be no one out there looking for baby Emmanuel except for us,” Bianco said after some social media broadcasters visited locations relevant to the case, ostensibly to help look for his remains.

“All you’re going to do is complicate things in the future,” the sheriff said.

It used to be that people who traded in true crime stories and shared conspiracy theories had to go out of their way to find their material and like-minded people.

“Now they come to us,” said Whitney Phillips, associate professor of information and media ethics at the University of Oregon’s school of journalism and communications.

As more people engage with stories about murder and mystery, social media algorithms designed to keep readers online create a feedback loop of related content, which is where creators jump in to offer updates that grow their audiences.

“These kinds of stories about crime, they become content — which immediately raises all kinds of ethical issues,” Phillips said. “Because what you’re talking about is real-life violence. It’s real-life trauma. It’s real-life destruction of maybe multiple people’s lives.”

There are two primary groups of people who interact with true crime content, Phillips said: everyday internet users, and those attempting to build a brand.

When the brutal slaying of four people in an Idaho home by Bryan Kohberger was still a mystery, online sleuths combed publicly available information to identify their own suspects.

When travel vlogger Gabby Petito was killed by her fiance, the case became a launchpad for some true crime influencers.

“You had a bunch of people who were just regular people online, who latched onto the story early and they were able to build their brands,” Phillips said. “Then they became true crime influencers from that, then branched out and started to engage with more true crime stories and monetize off of that.”

The search for Emmanuel started Aug. 14 when Rebecca Haro, 41, reported her infant missing and said she’d been attacked in a parking lot in Yucaipa while changing her son’s diaper.

She told authorities she’d been knocked unconscious and when she came to, Emmanuel was gone, according to the San Bernardino County Sheriff’s Department.

But two days later, authorities announced that Emmanuel’s mother had contradicted herself while talking to investigators and that they were “unable to rule out foul play” — triggering an avalanche of suspicion onto Rebecca Haro and, soon after, her husband.

Jake Haro, 32, has been on probation after pleading guilty to felony willful cruelty to a child in connection with serious, permanent injuries to his daughter in 2018, according to court records.

He pleaded guilty in 2023 and was sentenced to jail followed by time in a work-release program in lieu of four years in prison, records show. But a superior court judge suspended the prison sentence.

At a recent news conference, Riverside County Dist. Atty. Mike Hestrin said suspending Haro’s prison sentence had paved the way to Emmanuel’s death.

“If that judge had done his job as he should have done, Emmanuel would be alive today,” Hestrin said. “That’s a shame and it’s an outrage.”

The Haros made their initial court appearance in Riverside on Aug. 26 to a packed courtroom, a group of reporters and a TV news camera broadcasting the hearing. Although Emmanuel was reported missing in San Bernardino County, authorities said they believe he was the victim of long-term abuse in his home in Riverside County that ultimately led to his death.

Among those gathered for the initial hearing was Ahmed Bellozo, a self-described independent journalist who runs the popular TikTok account “On The Tira,” where he posts daily videos on the Haro case. There is a link to his online store, where he sells shirts, hoodies, hats and stickers. All of the store items were recently sold out.

Videos on Bellozo’s account show him visiting the Haro home, where he was greeted by fans, an area in Moreno Valley where authorities looked for Emmanuel’s remains and the parking lot in Yucaipa where the baby was reported missing. In one clip, Bellozo interviewed two women who work at the strip mall and asked one if she could provide security camera footage from the day of Emmanuel’s disappearance.

Asked about the role the media has played in the case, the Riverside County Sheriff’s Department aimed to distinguish between reporting and rumor-mongering.

“It is essential to recognize that misinformation, regardless of its source, can create unnecessary fear, confusion, and mistrust within the community,” the department said in a statement. “We appreciate the important role that journalists play in fact-checking and reporting responsibly. In contrast, the rapid spread of unverified information by social media influencers can lead to reckless speculation that interferes with the pursuit of justice.”

According to an August Pew Research Center study, about 26% of Americans consider people who post about news on social media “journalists” while 50% say they are not and 23% aren’t sure.

One of those who says he’s trying to do it the right way is Jimmy Williams, a self-described independent journalist from Chesapeake, Va., who runs the true crime YouTube channel Dolly Vision.

“I’ve been out here for three days,” he said outside the Haro home the day of their arrest.

The case stood out to him because of the mother’s statements, the father’s past child abuse case and the fact that authorities said they could not rule out foul play.

“In a missing kid’s case, there shouldn’t be that many red flags,” Williams said.

As an independent journalist and husband to a private investigator, he said, he holds his YouTube channel‘s content to a higher standard.

“Some of these people are a little crazy and they get out there and they start to instigate things and try to create a scene so it brings them more clicks and views,” Williams said of those he doesn’t consider serious journalists.

A quick search for the hashtag #EmmanuelHaro on social media will produce scores of news clips and videos of commentators opining about the case.

Since the Haros first appeared in court, Bellozo has created more than a dozen videos.

He posted one of himself and a group of people in a parking lot, announcing they’d created their own search party to look for Emmanuel’s remains.

He followed that up with a video that, with suspenseful horror music in the background, showed a vehicle driving down the 10 Freeway, with a caption reading: “This is the road to Emanuel’s house in Cabazon, California,” misspelling the infant’s name.

Early on in his coverage, he’d erroneously reported that Emmanuel’s body had been found.

Bellozo winced when asked about the error and said medication he’s taking for his cancer treatment has affected his judgment.

“This is taking a toll on me,” he said.

After the couple’s hearing, Bellozo shouted: “Hola” at Rebecca Haro as she was led out of the courtroom. It was the same greeting the mother said the alleged kidnapper uttered to her before taking her son.

A group of sheriff’s deputies briefly detained him.

Outside the courthouse, Bellozo apologized on camera to his viewers for the outburst. He was then mobbed by fans who wanted to take a selfie and thank him for his work.

©2025 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments