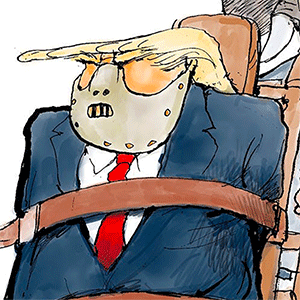

Trump tariffs face threat at Supreme Court -- over rulings that blocked Biden

Published in Political News

A legal argument that the U.S. Supreme Court used to foil Joe Biden on climate change and student debt now looms as a threat to President Donald Trump’s sweeping tariffs.

During Biden’s presidency, the court’s conservative majority ruled that federal agencies can’t decide sweeping political and economic matters without clear congressional authorization. That blocked the Environmental Protection Agency from setting deep limits on power plant pollution and the Education Department from slashing student loans for 40 million people.

The concept — known as the “major questions doctrine” — is now playing a central role in the case against Trump’s unilateral imposition of worldwide import taxes. With Supreme Court review all but inevitable, the justices’ willingness to employ the doctrine against Trump may determine the fate of his signature economic initiative.

The U.S. Court of International Trade cited the Biden-era rulings and the major questions doctrine when it ruled 3-0 last week that many of Trump’s import taxes exceeded the authority Congress had given him. The challenged tariffs would total an estimated $1.4 trillion over the next decade, according to the nonpartisan Tax Foundation.

Critics say the administration’s tariffs would have an even bigger impact than the estimated $400 billion Biden student loan package, which Chief Justice John Roberts described as having “staggering” significance in his 2023 opinion invalidating the plan.

“If this is not a major question, then I don’t know what is,” said Ilya Somin, a professor at George Mason University’s Antonin Scalia Law School and one of the lawyers challenging the tariffs. “We’re talking about the biggest trade war since the Great Depression.”

Until they were partly suspended, Trump’s April 2 “Liberation Day” tariffs marked the biggest increase in import taxes pushed by the U.S. since the 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariffs and took the U.S.’s average applied tariff rate to its highest level in more than a century. The prospect of that massive tax increase and the resulting economic shock roiled financial markets and prompted fears of imminent recessions in the U.S. and other major global economies.

Presidential exception

The administration contends the major questions doctrine doesn’t apply when Congress gives authority directly to the president, rather than to an administrative agency. The government also says the doctrine is inapt when the subject is national security and foreign affairs – policy areas where the president has long been recognized to have broad powers.

“No one doubts the significance of the challenged tariffs, but significance alone does not implicate the major questions doctrine, otherwise, it would apply to countless government actions, including every emergency statute,” the Justice Department said in a filing at the Court of International Trade.

The legal clash centers on Trump’s power under the 1977 International Emergency Economic Powers Act, which says the president may “regulate” the “importation” of property to address an emergency situation. The Court of International Trade said those words weren’t clear enough to legally justify Trump’s taxes given that the Constitution gives the tariff power to Congress.

In addition to major questions, the panel also invoked the nondelegation doctrine, a related conservative-backed legal theory that says lawmakers can’t give away their constitutional legislative and taxing powers.

The two doctrines together “provide useful tools for the court to interpret statutes so as to avoid constitutional problems,” the trade court said. “These tools indicate that an unlimited delegation of tariff authority would constitute an improper abdication of legislative power to another branch of government.”

The ruling is now on temporary hold while a federal appeals court considers whether to keep the tariffs in force as the legal fight continues.

Ideological split

So far, the major questions doctrine has divided the Supreme Court cleanly along ideological lines. The six conservative justices were united when the court first used the phrase in a 2022 ruling that said the EPA overstepped its authority with an ambitious emissions-reduction program during Barack Obama’s presidency. The majority said it was doing nothing new by subjecting the plan to extra-tough scrutiny.

“We ‘typically greet’ assertions of ‘extravagant statutory power over the national economy’ with ‘skepticism,’” Roberts wrote, borrowing words from a 2014 ruling. Roberts said the court used similar reasoning, though without the “major questions” label, when it blocked Biden’s pandemic eviction moratorium and his vaccine-or-test mandate for workers.

The court’s liberals accused their conservative colleagues of creating a convenient exception to their usual laserlike focus on statutory text.

“The current court is textualist only when being so suits it,” Justice Elena Kagan said in dissent in the climate case. “When that method would frustrate broader goals, special canons like the ‘major questions doctrine’ magically appear as get-out-of-text-free cards.”

The sharp ideological divide masks a more subtle split among the court’s conservatives about the purpose of the major questions doctrine. Justice Amy Coney Barrett has described it as a tool for ascertaining the most natural reading of a statute, while Justice Neil Gorsuch has cast it as a means of keeping Congress and the president in their proper constitutional lanes.

The key question now is what the court will do with the major questions doctrine when it comes in the context of tariffs and a Republican president who appointed three of the justices.

“The court has not been at all transparent about the grounds on which it will invoke this doctrine,” said Ronald Levin, an administrative law professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “It’s left its options completely open.”

———

(With assistance from Shawn Donnan.)

©2025 Bloomberg L.P. Visit bloomberg.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments