Commentary: DEI is a path to meritocracy, not an alternative

Published in Op Eds

In the move to obliterate diversity, equity and inclusion, one word — merit — has stood out as an effective cudgel. The president’s executive orders claim to restore “meritocracy” and “merit-based opportunity” from the scourge of DEI.

Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth condemns the “toxic ideological garbage” of inclusive practices while lauding the idea of “merit only.” Activists against diversity efforts echo this theme.

Heather Mac Donald, author of the book “When Race Trumps Merit,” states: “At present, you can have diversity, or you can have meritocracy. You cannot have both.” When the chief executive of Scale AI argued that DEI should be replaced by MEI (merit, excellence and intelligence), Elon Musk amplified the proposed shift as “great.”

As scholars of diversity initiatives, we agree that merit should be a top priority in admissions, hiring and promotions. A major reason our society still needs diversity, equity and inclusion, after all, is to overcome a long history of unfairly assessing people based on criteria other than merit.

Such unfairness can arise from decisions based on disadvantage, such as racism or sexism. It also arises from decisions based on advantage, such as nepotism or pay-to-play arrangements. Promoting merit always has been intertwined with promoting equal opportunity, and we need to make that connection clearer in the public debate. Those of us who support a more egalitarian society should be able to reclaim the “merit” buzzword from the anti-inclusion ideologues.

A significant obstacle to doing this has been a flank of the pro-inclusion community that has an allergy to the word “merit,” thus feeding the misconception that it belongs to their opponents. Some advocates for diversity initiatives argue that merit and meritocracy are “hollow,” a “myth” or “the antithesis of fair”; they accept the detractors’ framing of the issue, in which an inclusion-centered approach is an alternative to a merit-based system. Many diversity leaders have told us they have a visceral negative reaction to the term “merit” and urge advocates not to use it.

We find that inclusion advocates who chafe at emphasizing merit usually do so for some mix of three reasons.

First, the concept of merit leaves a lot of discretion, so the dominant group that defines merit will abuse that discretion to favor itself. In one study, a sociologist asked white Californians how much weight college admissions officers should place on high school grade-point average. Respondents were much more likely to emphasize GPA when primed to perceive Black students as white applicants’ main competition for college slots. When primed to perceive Asian American students as the main competition to white students, GPA abruptly became less important in the respondents’ minds.

This result is likely because of stereotypes associating Asian American students with higher GPAs and Black students with lower GPAs. As the researcher observed, the difference in responses from white people “weakens the argument that white commitment to meritocracy is purely based on principle.” Instead, people twist the definition of merit to advantage their own group.

Second, critics point out that the markers identified with merit often are unearned. Factors such as family connections and wealth make it easier for some to develop capabilities than others.

In another study, participants were told about a hiring committee focused on “getting the most qualified candidate” for a role. The committee chose one candidate, Jim, over another, Tom, because Jim had better grades, internships and extracurricular activities. When participants learned that Tom was just as hardworking as Jim but lacked the family support and resources to attend good schools, study without a part-time job or complete unpaid extracurriculars, participants rated the supposedly merit-based hiring decision as significantly less fair.

A third objection is that merit overemphasizes what people can do, rather than their innate worth as human beings. In his book “The Tyranny of Merit,” philosopher Michael Sandel spotlights the dangers of the “meritocratic imperative — the unrelenting pressure to perform, to achieve, to succeed.” Such pressure means even the people who have the genetic or environmental supports necessary to succeed in the meritocracy are run through a “high-stress, anxiety-ridden, sleep-deprived gauntlet” to emerge victorious.

This imperative hurts not just individuals but also society as a whole, because it cultivates a humiliating sense of failure among those who lose the meritocracy contest, and a self-congratulatory attitude among the people who win it. This result fuels populist anger among society’s “losers” and a high tolerance for inequality among its “winners.”

Given these blistering critiques, why are we still fans of merit? Our central answer is what we call the “social reliance” argument. If you go to a doctor, you expect that they have gone to medical school and have the training to treat you with expertise that exceeds that of a layperson scanning WebMD. If you get on a plane, you trust the pilot can safely fly it, and that they’ve gone through hundreds of hours of training to earn that trust. When you use your microwave, boot up your computer or cross a bridge, you assume it won’t explode, electrocute you or collapse. A well-functioning society requires such reliance, and to satisfy it, we need merit-based assessments.

The three critiques, however, can guide us toward a more nuanced vision of merit. For starters, we all need to be eternally vigilant about how bias might seep into merit-based assessments and ensure that systems are in place to limit this.

Decision makers also could consider how diversity can be a component of merit, rather than antithetical to or independent of it. Black patients have better outcomes when treated by Black physicians. The accuracy of clinical drug trials depends on a diverse group of participants testing the drug. Teams composed of people from diverse backgrounds are smarter and more innovative than homogeneous ones.

Next, when merit is unearned, inclusion advocates can balance considerations of merit and fairness. A hiring manager might fairly pick a candidate who has potential but has had limited opportunity to fulfill that potential.

Finally, advocates can respond to the argument that merit overemphasizes achievements and undervalues people. Here the key is to think about different areas in which merit matters more or less. Public schools should admit all children, rather than limiting who can attend based on their intelligence or skills. Hospitals should treat patients based on need, not based on whether they “deserve” treatment because they’ve pursued a healthy lifestyle. Athletic organizations commonly distinguish between competitive leagues that select for ability and open leagues that emphasize fun for all.

We don’t want to put merit at the center of human life. Instead, we claim more modestly that merit should play an important role in common institutional decisions, such as hiring, access to sought-after educational and professional opportunities, and conferral of awards and prizes. In these domains, embracing merit may have its flaws.

But just like the adage that democracy is the worst form of government except all the others, merit is the worst form of assessment except all the others. Think of the major alternatives, which include popularity, wealth, cronyism, nepotism or a lottery system. Merit is clearly superior to these other options.

In the broader cultural debate over diversity, equity and inclusion, “merit” is inescapable. Whichever side successfully claims merit will win this war of ideas.

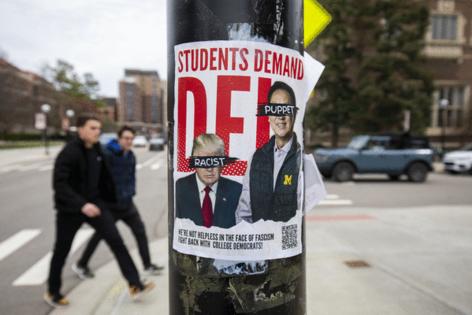

That’s why we applaud the strategy adopted by Democratic state lawmaker Erin Byrnes after the Michigan House of Representatives passed a bill last year requiring state agencies to hire employees based on merit. State Republicans touted the measure as “anti-DEI legislation,” stating: “There is no place for DEI in our government.”

Yet Michigan Democrats also supported the measure. Byrnes noted the legislation would “create opportunity by eroding the barrier of the old boys’ club as we work toward a more equal playing field for all Michiganders.” Speaking after the vote, Byrnes struck exactly the right note: “House Republicans in Michigan voted yes on a DEI bill. I love that for them.”

____

Kenji Yoshino and David Glasgow are the faculty director and executive director of the Meltzer Center for Diversity, Inclusion, and Belonging at New York University School of Law. They are co-authors of the forthcoming “How Equality Wins: A New Vision for an Inclusive America,” from which this article is adapted.

_____

©2026 Los Angeles Times. Visit at latimes.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments