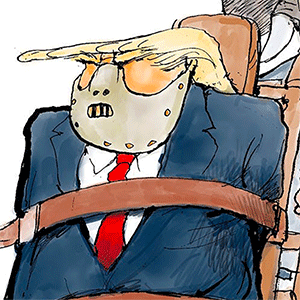

Commentary: Boat attack shows that Trump doesn't know what he wants in Venezuela

Published in Op Eds

On Sept. 2, the Donald Trump administration killed 11 people by destroying a boat that allegedly was being used by the Venezuela-based Tren de Aragua gang to transport narcotics to the United States. The strike came with a message from Secretary of State Marco Rubio: Those who dare to ship drugs to the United States risk their lives.

But if the military operation in the southern Caribbean was meant to highlight just how serious the White House was about curtailing Latin America’s drug cartels, it also demonstrated the haphazard, disjointed and downright confusing policy Washington has with respect to Venezuela.

During the Trump administration’s first few weeks in office, it appeared as if Washington and Caracas, adversaries for the last two decades, were in the process of mending relations. On Jan. 31, Richard Grenell, Trump’s special envoy, met with Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro and returned with six Americans who were languishing in Venezuela’s prison system. The United States and Venezuela struck a migration accord, with Maduro agreeing to accept Venezuelan deportees. And in July, Trump provided Chevron, the U.S. energy company, with a temporary license to resume pumping Venezuelan oil for export to the United States.

Yet in the grand scheme, U.S.-Venezuelan relations are fast deteriorating. The Trump administration blames Venezuela reneging on the migration deal. In August, the U.S. Justice Department doubled the bounty on Maduro, who in 2020 was indicted on a slew of narcotrafficking charges, to an astounding $50 million. Meanwhile, eight U.S. warships are currently stationed near Venezuela’s shores. The Trump administration also deployed 10 fighter aircraft to Puerto Rico, giving the White House even more resources to continue the kinds of militarized counternarcotics operations we saw last week.

The outstanding question looms: What exactly does the Trump administration want to achieve in Venezuela? We don’t have a clear answer. And that’s a problem because if the objectives aren’t clear, the policy will remain listless.

Right now, Trump seems utterly conflicted. During his first term, he adopted a maximum pressure strategy consisting of economic sanctions against Venezuela’s oil industry and diplomatic recognition of the anti-Maduro political opposition. The strategy was prefaced on the hope that, with time, Maduro would be removed from power.

Yet a year after Maduro survived a coup attempt, Trump switched his tactics, hinting he would consider having a summit with the Venezuelan strongman. His decision to walk back that statement 24 hours later only highlighted just how discombobulated Trump’s policy was.

Thus far, Trump’s second term isn’t much different from his first. Part of this can be chalked up to personnel; Rubio is a hard-liner who still believes in regime change in Caracas, whereas Grenell is more amenable to doing business with Maduro. Sometimes, those two positions have clashed.

But individual personalities are only part of the story. Ultimately, the source of the confusion can be traced to Trump’s ambitions. He’s simply trying to do too much in Venezuela. When everything is a priority, nothing is a priority.

Take Washington’s latest pressure tactics against Maduro. With the destruction of a cocaine-carrying vessel that reportedly took off from Venezuela, the Trump administration has made it abundantly obvious that weakening drug trafficking organizations is a top national security priority. Trump also views Maduro as one of the region’s biggest profiteers of the drug trade, although the extent of Maduro’s relationship with narcotrafficking is a matter of dispute.

However, Trump has other things he wants to accomplish besides cracking down on the cartels. His immigration agenda, which entails mass deportations of undocumented immigrants, relies almost entirely on countries accepting their own nationals. Maduro has cooperated with this scheme to an extent, but it’s difficult to envision the Venezuelan government continuing to do so if the U.S. military goes through with using force against his government or Venezuelan territory. In fact, the exact opposite is likely to occur: Reducing or outright nullifying any cooperation on migration would be one of the levers Maduro could pull in retaliation. This, in turn, would add further complications for Washington at a time when many of its deportation schemes are held up by the courts.

The same can be said of democracy promotion. Restoring an open, representative political system in Venezuela has been a U.S. policy objective since the days of the late Hugo Chavez. Maduro’s fraudulent election victory in 2024, which the United States, Europe and many Latin American countries refuse to recognize, merely elevated the issue. Maduro, though, equates any U.S. democracy promotion efforts as thinly disguised attempts at regime change, which means he has little incentive to work with the United States on anything as long as the Trump administration is aiming to displace him.

In other words, if Trump wants to see any success in Venezuela, he needs to determine which goals are most important to U.S. national security interests and which can wait for another day. A refusal to prioritize will lead to a set of competing, ad hoc actions, with disappointment and frustration the ultimate result. And that’s precisely what we have today.

There’s no disputing that Maduro is an incompetent head of state who has stolen elections, jailed his political opponents and partnered up with countries (Cuba, Iran, Russia and China, to name the most significant) Washington finds unsavory. But the United States deals with plenty of despicable regimes whose democratic bona fides are weak to nonexistent and whose human rights practices are troublesome, if not abhorrent. Sometimes to be the most effective, you need to deal with the people who are in power regardless of legitimate moral qualms.

Trump frequently categorizes himself as a man who sees the big picture and has a natural ability to get deals others couldn’t possibly dream of. Venezuela will be an apt case study of whether Trump’s pseudo-realist tendencies are fake or genuine.

____

Daniel DePetris is a fellow at Defense Priorities and a foreign affairs columnist for the Chicago Tribune.

___

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments