Commentary: Billion-dollar Powerball jackpots are all about marketing, not money

Published in Op Eds

Two winners in Missouri and Texas split the $1.787 billion Powerball jackpot (with a cash option of $820 million), which is the second largest ever recorded. The Mega Millions lottery jackpot is also quite large, reaching over $358 million (with a cash option of $164 million), as of Monday afternoon’s estimate. All these numbers are far beyond what the average person buying a lottery ticket can imagine. Yet jackpots of these magnitudes are more about marketing and selling tickets, not about acquiring wealth.

To put these numbers into perspective, a person who earns $100,000 per year over a 40-year career will earn $4 million during their lifetime, far less than either of these jackpots.

The dream of winning a lottery jackpot drives people to use their hard-earned money to grab the chance for what they perceive to be a pathway to personal wealth and a life filled with financial freedom and luxury. Unfortunately for almost every person who indulges themselves with a ticket, their dream is rarely realized.

At just a few dollars per ticket, some will argue that buying a lottery ticket is a cheap form of entertainment. The issue is whether just one ticket is purchased or many throughout the year.

So what is the payback for these indulgences?

Setting aside the jackpot prize and the Power Play multiplier, every $2 Powerball lottery ticket returns around $0.32 on average among the non-jackpot prizes, which can be calculated using the data reported on the lottery’s website. Such low returns are not widely discussed for the non-jackpot prizes.

A rational analysis like this is not what regular lottery players think about or even want to hear. That is why as the jackpot climbs, interest in the lottery also grows, fueled by the lotteries themselves and amplified by the media. This drives ticket sales sky-high, with sales for last Saturday’s drawing exceeding $489 million.

Evidence that lottery ticket buyers act irrationally when the jackpot soars is that Power Play sales also surge, even though the extra dollar paid for the Power Play multiplier has no effect on the jackpot prize.

Some will say that if you do not buy a ticket, you can never win the jackpot. That is of course true. Yet the likelihood of winning the jackpot is so low (1 in 292,201,338, to be exact) that focusing on it distorts what the actual payout for almost everyone will be, which are the non-jackpot prizes.

How low are these jackpot odds? A person is around 240 times more likely to be struck by lightning each year than to win the jackpot.

The case study to confirm this point is Jerry and Marge Selbee. Jerry uncovered a loophole in Michigan and Massachusetts lotteries such that when the jackpot reached a certain level because it has not been won for several drawings, the non-jackpot payouts would be adjusted upward, making the expected payout per ticket positive for lottery players a few times every year. However, exploiting this advantage required them to purchase millions of tickets. Despite all such tickets bought, they never won the jackpots (as Marge noted in the movie “ Jerry and Marge Go Large”), methodically winning the non-jackpot prizes for profit.

Given the miniscule expected non-jackpot payout per ticket, buying a ticket is equivalent to voluntarily paying a tax. Moreover, since the majority of people who regularly purchase lottery tickets are low-income earners, this makes such a tax highly regressive.

So who were the big winners this past week with the record jackpot up for grabs? The people who stayed on the sidelines and did not buy a ticket. They also benefited from all the tickets purchased, given that as much as 38% of the proceeds go to state public funds.

In general, the best way to win any lottery is by never buying a ticket. That may not sound as exciting as dreaming about the jackpot, which you are not likely to win anyway.

____

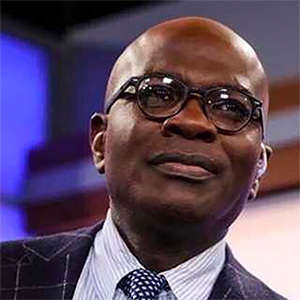

Sheldon H. Jacobson, Ph.D., is a computer science professor in the Grainger College of Engineering at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. A data scientist, he uses his expertise to address issues in public policy and explore sports analytics.

___

©2025 Chicago Tribune. Visit at chicagotribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments