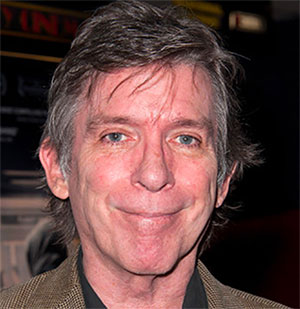

From 'Hedwig' to head of the class, John Cameron Mitchell leads UM film course

Published in Entertainment News

DETROIT — In John Cameron Mitchell's classroom, students' phones go in a popcorn bucket.

The actor and filmmaker, best known for his 2001 cult hit "Hedwig and the Angry Inch," is a visiting professor in the University of Michigan's Department of Film, Television, and Media, teaching a course this semester he's labeled "Problemagic Cinema." Class kicked off Monday at Ann Arbor's State Theatre, where Mitchell — his hair colored half black, half white — first asked his students to kindly part with their devices and place them in an empty popcorn bucket, where they could pick them up at the conclusion of class.

The bucket wasn't thought about ahead of time, it was just what was around. But the important thing is that phones aren't in students' hands, or silently tempting them in their pockets, so their attention is undivided. Laptops aren't allowed either; note-taking occurs in notebooks Mitchell provided for the students, with pens he brought for them as well. He's gone full analog, which is about as punk as it gets in 2025.

Mitchell, a perennially youthful 62 years old and a self-proclaimed "punk, queer grandpa," isn't just being a crank about technology. Distractions brought on by phones and digital culture at large have fractured our attention spans and our abilities to connect, not only to one another but to art, he argues. And so he's trying to bring back a sort of pre-digital form of attention, a 1970s kind of attention, if only for the span of his once-weekly, four-hour class sessions.

"I really feel we wouldn't be where we are, in many ways, without digital culture," says Mitchell, which he means in a not positive way. "It has also served to disconnect us. It's supposed to connect us, right? But it ends up disconnecting us from our feelings, and spackling in the pauses in our life. The idea of being bored or just taking a pause is anathema to us, so we have to quickly fill it with texts, or whatever. But it's in those pauses that memory establishes itself. It's also where emotion fills in, and it's where empathy grows.

"I want my students to feel again," says Mitchell, chatting outside a downtown Ann Arbor café on Monday during a short class break. "That's why I'm taking away their phones, and seeing what takes root."

Attention spans aren't the only '70s throwback in Professor Mitchell's class. The course, which includes one film screening per week, contains a number of '70s titles, including Bob Fosse's "All That Jazz," Sidney Lumet's "Network," John Cassavetes' "A Woman Under the Influence" and Robert Altman's "Nashville."

At Monday's introductory class, students were greeted with "Harold and Maude," Hal Ashby's 1971 classic about the unlikely friendship that develops between a death-obsessed youngster and his nearly 80-year-old kindred spirit. Mitchell uses the relationship that develops between the pair as a metaphor for a lot of relationships in his life, from individuals to works of art with which he connects, and he hopes his students take the film and its message to heart, as well.

From army bases to 'Hedwig'

Mitchell grew up an army brat, which he says allowed him — or forced him, depending on your perspective — to get along with all types of people. He studied theater at Northwestern University, where one of his professors, Frank Galati, made a lasting impression on him, so he knows the difference teachers can make in students' lives.

Mitchell acted in many movies and TV series throughout the '80s and '90s, until he got a chance to bring his off-Broadway musical "Hedwig and the Angry Inch" to the big screen in 2001. The queer rock and roll musical, about a gay East German rock star whose music is stolen by his young musical protege, was a Sundance sensation and a critical hit, and audiences followed once the film hit the DVD aftermarket, propelling it to cult status.

It may not have ever been a blockbuster, but it found its audience, and Mitchell is frequently approached by people showing him their Hedwig tattoos. "Who's got a tattoo of '3rd Rock From the Sun?' Or 'Argo?'" Mitchell asks, illustrating the difference between a piece of art with a big audience and a piece of art with a loyal audience.

He followed "Hedwig" with the sexually explicit "Shortbus" in 2006 and the stark 2010 grief exploration "Rabbit Hole," as well as the 2017 comedy "How to Talk to Girls at Parties." He continued to act — he played a book editor on "Girls" and Joe Exotic on the "Tiger King" tale "Joe vs. Carole" — and he's recently created a series of dramatic podcasts, including this year's highly satirical "Cancellation Island."

The Netflix-ization of Hollywood has made it harder to get independent films off the ground, he says, which is partially what has pushed him to the world of dramatic podcasts. But he says stories, no matter the form they take, are as important as ever, which is partially why he's taken on a professorial role, mentoring the next generation of filmmakers.

The U-M gig came up after Mitchell toured 14 college campuses earlier this year, including U-M, talking to audiences about the current state of storytelling. He met with Colin Gunckel, the chair of U-M's School of Film, Television, and Media department, who informed Mitchell of the John H. Mitchell (no relation) Visiting Professor in Media Entertainment role; previous guest professorships were held by Kemp Powers, co-director of "Soul" and "Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse," and Janet Leahy, the former "Mad Men" producer and "Cheers" and "Gilmore Girls" writer.

Gunckel says Mitchell is a perfect fit for the job.

"He's done it all, and he has such a deep knowledge and experience. It's exciting to have him here, and it's exciting just to have his kind of presence," Gunckel says. "He's had a really extraordinary career; he's done television, film, theater, Broadway, music, and he has a unique way of bringing all those things together.

"Just the fact that he's such a multi-talented individual, he can talk to so many different kinds of students, whether they're interested in acting or making films or having the kind of hybrid, multimedia career that he's had. I think he can give students a really great sense of what's possible," says Gunckel. "I think he opens up other possibilities for them, and that's exactly what we want for our students at this point in their lives, is to be exposed to different opportunities and possibilities."

Lust for life

The fact that Mitchell has landed in the hometown of one of his (and Hedwig's) idols, Iggy Pop, is not lost on him. He keeps his punk roots very close to his chest; at Monday's introductory class, he wore a Split Enz T-shirt, celebrating the '70s and '80s New Zealand prog rockers.

New Orleans is his home these days — he also keeps a place in New York — and Mitchell is flying in weekly to Ann Arbor for the classes. He's teaching a small pool of nine students, and he spent Monday connecting names with faces and those faces with their goals for the semester.

Peter Kotas of Detroit is taking the course specifically because it's being taught by Mitchell. "I love 'Hedwig and the Angry Inch,' I saw it on DVD shortly after it came out, and it's such an original movie that blends music and animation and a very raw live aesthetic," says Kotas, 38. He says from the class, he's hoping for "great stories from the guy that made 'Hedwig and the Angry Inch.' To be able to tap into that mind is an absolute blessing."

For Mitchell, he says connecting with students is inspiring. His college speaking tour earlier this year reminded him why he chose a life in the arts, and it's especially important now, a "specifically strange time," he says, when art is caught up in the whirlpool of everything else that's happening culturally and politically.

"Everything that I learned, stand for and do has been called into question, in terms of empathy," says Mitchell. "Art, for me, are the synapses that make those connections that empathy can flow through. Performing, narrative art, stories in any form — books, films, TV, anything — connected me to what I cared about, connected me to myself and connected me to the world. It was like a thread. Otherwise, I felt kind of cut off and pre-dead. So art was my Maude."

"Problemagic Cinema" — "problemagic" is Mitchell's preferred way of saying "problematic," the term used to describe today's prickly or "cancelled" words, ideologies and pieces of media — deals with films taking on social problems. He's aiming to get students to reject, or at least question, feelings that certain ideas are "problematic," turning those gateways into freeways, and opening up the dialogue around them.

He curated the syllabus — much like Hedwig drew up a syllabus of rock classics for his protege, Tommy Gnosis (Michael Pitt), to study from — from film classics from Hollywood's golden era, as well as world cinema he hoped would spark the creativity of his students.

The syllabus also includes Stanley Kubrick's "Dr. Strangelove," the 1996 Iranian film "A Moment of Innocence" and 2006's "The Lives of Others"; screenings are open to the members of the U-M community, but post-film discussions are reserved for students only.

As for tests, pop quizzes, etc., there won't be any. The students' only assignment for the semester is to make a short film, which will account for 60% of their grade. (Participation and attendance make up the other 40%.)

That final film can be anything from a two-minute movie composed of one shot — if that's the case, it better be a good shot, he jokes — to a 15-minute production with multiple speaking roles and settings. What he's looking for is clarity, creativity, and a piece of the individual student's vision to be expressed through the camera lens.

"If you make something through your body and mind, what comes out the other side might be s---, but it’s original. It’s your s---," Mitchell says. "No matter what your influences are, no matter who you’re imitating, if it comes through you, A) it’s creation, and B) it’s, sometimes, useful for others."

"Does the short have to be problematic?" one student asked Mitchell during Monday's class.

"No," Mitchell answered, although he liked where the student's head was at. "But if that's what you're thinking, you should follow that," he told him, a wry smile creeping across the professor's face.

©2025 The Detroit News. Visit detroitnews.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments