Asylum seekers, who came to US legally, navigate unexpected ICE detainments

Published in News & Features

MINNEAPOLIS — Moments before handyman Pablo Nieves was detained outside a Home Depot in Plymouth, he called his daughter, Valeria.

An Immigration and Customs Enforcement agent had shot and killed Renee Good in south Minneapolis the day before, and Valeria was queasy about going to school. Pablo tried to assuage her fears, telling her he’d just spoken to her counselor about transferring her to online classes.

They hung up. Pablo bought a load of building materials and loaded his car. Suddenly, federal agents blocked him in.

For five years, the Nieves family lived and worked in the United States with the federal government fully knowing their whereabouts. So it came as a surprise when ICE detained Pablo last month.

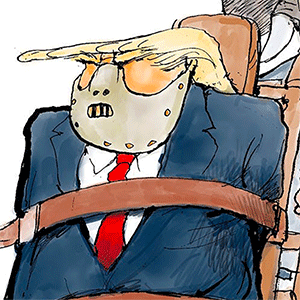

His experience highlights the increasing peril that immigrant families face as they try to navigate a confusing immigration system under President Donald Trump, where the rules around asylum-seekers are in constant flux.

Previous administrations allowed immigrants seeking asylum to remain in the U.S. while their case moved through the court system. But in Minnesota, the Trump administration detained and transferred people to out-of-state detention centers before they have received final removal orders.

Pablo and his family arrived in the United States from Venezuela legally on a nonimmigrant visa in 2018 and applied within a year for asylum from persecution in their home country. Under the Biden administration, the U.S. granted as many as 76% of asylum applications from Venezuelans, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse at Syracuse University. But that has since flipped to a 76% rejection rate this year.

Since the Nieves family’s applications are pending, their lawyer, Kelsey Allen, declined to share why they asked for asylum. But with growing asylum backlogs each year, Pablo overstayed his visa, a civil offense.

The federal government never issued a final order of removal for Pablo during Trump’s first term or President Joe Biden’s term. He met with immigration officials upon request. He has no criminal record and was never taken into custody.

That changed this year. Pablo — who did maintenance for a chain of Twin Cities Spanish immersion preschools — was taken to the Whipple Federal Building on Jan. 8, then flown to a Texas detention center where he was held for two weeks.

Pablo told the Minnesota Star Tribune that it seemed like the federal government wanted detainees to self-deport by eroding any hope they had in their immigration claims.

“There was a lot of uncertainty and fear,” he said through a translator. “People would begin to break.”

Some have been deported. But in other cases, lawyers have successfully argued there was no reason to take these people into custody.

“The frustrating thing of detaining asylum-seekers needlessly is it’s a lot of resources they’re expending, shipping people from Minnesota to Texas and back up to Minnesota, and adding all of these bond cases to already overburdened immigration judge dockets,” said MacKenzie Heinrichs, an asylum expert with the University of Utah’s S.J. Quinney College of Law.

Traditionally, a criminal conviction is the only reason why immigration officials would detain someone without a removal order, Heinrichs said. But now, “They just seem to be picking up people who have pending asylum applications, putting them in detention, and then a lot of those folks are getting out on bond because they really shouldn’t be in detention in the first place,” she said.

Nieves may have been lucky to have been released at all.

A recent court ruling allows the Trump administration to indefinitely hold immigrants in detention, which could affect thousands imprisoned in Texas camps regardless of how long they’ve lived in the country.

In a statement, the Department of Homeland Security celebrated the ruling and said it is “working rapidly overtime” to deport people without status despite a historic number of injunctions by what it called “activist judges.”

“Politicians and activists can cry wolf all they want, but it won’t deter this administration from keeping these criminals and lawbreakers off American streets — and now thanks to the Big Beautiful Bill, we will have plenty of bed space to do so,” DHS assistant secretary Tricia McLaughlin said in the statement.

Pablo’s detainment coincided with the deployment of thousands of federal agents to Minnesota in early January. Many immigrant families went into hiding as protests flared across the state.

Simultaneously, Spanish immersion day cares started reporting ICE vehicles circling their facilities, staging in their parking lots and detaining staff. Parents organized rides for noncitizen teachers.

They also raised money for Pablo’s legal fight to stay in the country.

His absence unmoored his wife, Ninoska Urbaneia, who taught at the Spanish immersion preschool where Pablo worked, and their daughter Valeria. At 16, Valeria suddenly found herself sorting through her father’s personal accounts and tax records to equip their immigration lawyer.

During an interview with the Star Tribune in January, Valeria recalled how scared she felt as Operation Metro Surge peaked. Both of her parents had work permits, steady employment and pending asylum cases, but the federal government’s largest-ever immigration crackdown was sweeping up families that sounded like theirs.

On their final call on Jan. 8, Valeria told Pablo she loved him, not knowing that right after they hung up, federal agents would detain her father and shackle him in a crowded holding cell at the Whipple Federal Building near Fort Snelling.

The next day, the guards gave Pablo two minutes to call his family, but he didn’t have much to share, saying he didn’t know what they were going to do with him.

“It hurt me a lot, because I’ve never heard my dad cry,” Valeria recalled. “I didn’t know if he had eaten, or if he was okay.”

The following day, the family learned Pablo was transferred to the nation’s largest immigration detention center in El Paso, Texas.

The Nieves family’s immigration lawyer, Allen, argued that Pablo wasn’t a flight risk nor a danger to the public. Preschool staff and parents wrote dozens of letters pleading for his return.

It would take time, though, to schedule a hearing to argue for his release.

Valeria and Ninoska spoke with Pablo only a handful of times over the next two weeks — two minutes here, three minutes there. They tried to keep his spirits up.

Meanwhile Ninoska took time off and Valeria continued online instruction. They moved in with relatives, relying on the kindness of family friends for groceries while they kept out of sight for fear they could be detained as well.

Ninoska told the Star Tribune she missed her students and was worried about losing her job, despite the school’s support.

“I also feel for people that maybe don’t have the support that we do,” she said, while her daughter translated. “I think they wouldn’t be able to afford [a lawyer] ... I don’t think they would be able to fight.”

Pablo got his court hearing and order for release on Jan. 16. It took another week to process his bond payment.

But the ordeal wasn’t over.

The El Paso facility released him on the street in his prison uniform, without his IDs or employment authorization documents, Pablo said.

Friends helped him travel back to Minnesota by way of Phoenix. On Jan. 24, he reunited with his family in the Twin Cities.

They cried and hugged. As Pablo sat down at the dinner table, Ninoska and Valeria didn’t leave his side. Fifteen days, they kept repeating, noting his time in detention. But even in the relief of their reunion, an air of gloom hung between them. Pablo was weary, his stare long and distant.

Pablo spoke tepidly about his experience in Texas. He said he was detained with more than 60 others in a cold room with blank walls and bright lights. Only those with lawyers could make any phone calls, he said.

The guards summoned them by whatever names they wanted and wouldn’t say if they were being deported or not. Some younger men refused to sleep and would pace the length of the room, back and forth, as a sort of defiance. A lot of people opted to self-deport.

“Many lost face, crying, crying out to God,” Pablo said. “There are people who have been in there a month, two months or more. Hopefully there are answers to their cases.”

A few days after their reunion, Valeria said it pained her to see her dad so emotional.

“I was so happy, but at the same time ...” Valeria said, her voice cracking. “Hearing all the conditions that he had to go through was very heartbreaking. But we’re finally home, and we’re settled down.”

With that part of their ordeal over, little has changed about the Nieves family’s status. Pablo is free to live and work in his community. But he’s a little more damaged from the experience, and his legal bills cost his family and supporters thousands of dollars.

Throughout Operation Metro Surge, refugees and asylum-seekers with pending applications have been apprehended, sent out of the state and detained for indefinite periods of time after complying with notices to report for ICE check-ins and immigration hearings. When that happens, it leads people to question what incentive they have to obey immigration requirements, Heinrichs said.

Coupled with changes under the Trump administration to reduce the validity of work permits from five years to one year, asylum-seekers are facing conditions that could force many to seek “under the table” work, which opens this already vulnerable population to labor trafficking, she said.

“What employer is going to want to hire somebody who’s on a work permit through asylum when there’s no guarantee that they’re going to have work authorization for an extended period of time?” Heinrichs said.

As of Feb. 17, the monthlong window for DHS to appeal his release has closed, but the Nieves family’s asylum case continues. Pablo will also be expected to once again attend meetings with immigration officials, hoping that his asylum request is eventually accepted.

---------

—Minnesota Star Tribune photographer Elizabeth Flores contributed to this story.

©2026 The Minnesota Star Tribune. Visit at startribune.com. Distributed by Tribune Content Agency, LLC.

Comments